|

|

|

|

|

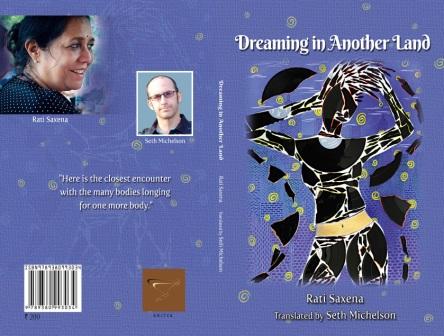

Dreaming in Another Land Rati Saxena - India Translated by Seth Michelson

My Sheet

That morning when I woke, I saw a small hole in my sheet, the result of being lost in sleep. So I struggled with silken thread throughout the day and by night had stitched a window for glimpsing a few, new dreams.

The next day I woke to a new hole and this time added paint to the thread. Before dark Iíd built a door.

My dreams could leave now and wander instead of gazing out a window, dreams freed to roam the entirety of the night. Each morning brought new holes; each day bustled with thread and paint.

Today my sheet is an enormous courtyard with a banyan tree filled with birds with beaks like red stars, though both sun and moon remain absent.

So I spend my mornings searching for holes where a sun and moon might be woven, not only in this galaxy but also across the many, layered others,

knowing at the end thereís a final hole through which to exit and join the great beyond

in a seamless realm of light.

The Body change

With my first step onto the seventh-story floor I removed the coolness like a shoe that Iíd brought from the courtyard painted with cow dung. I donned the new room like a sweater with windows, shelves, and walls, the surroundings climbing my body like bougainvillea.

Whenever moving between homes I carry bits of the old ones on my body.

The walls of the next home are made of sunlight that disappears with darkness. To put on this home is to enter dreamfulness as a road to reality.

At the final home, a pillow waits on my side of a shared bed beside a window facing south.

The south is the house of death. I make it my body and lie down on my pillow.

Now I am ready.

Mother Used to Save

At any moment, under any conditions, the storehouse of mother was never empty, she saved oils, grains, pickles, beans, salt in clay pots, glass jars of jaggery, all of it living for centuries in her magic storeroom, and available in an instant without a single ďOpen, Sesame!Ē

Mother saved flesh, too: on her waist and hips, for her seven hungry children, born one after another, and for the next generation: to love grandmaís soft, sweet feel.

And she saved stories, myths, unknown rhythms, steps for the grandchildrenís dreams, a way of keeping her with them after sheís long gone.

In her final moments, her last breaths left her daughters a home, through which she keeps dissolving like a sugar packet into water.

Before leaving

close all the doors, one by one,

hear them shut with a click, pat each knob farewell,

and try never to promise to return, not even by mistake,

donít fret over who next might pass through; each door itself decides this

before leaving wipe away each footprint and fingerprint, no longer needed by anyone,

before leaving, pack your things, bundle every rusted story

and decorate the table with memories of laughter

before leaving, check every book, throwing out the pressed flowers dried in their pages

before leaving erase every line, break open all the knots

and smile with strength until life comes to sit in the corners of your mouth

before leaving, close the final door, and the rest will close themselves

Dreaming in Another Land

He wanted her to smile the dream of living in another land.

He wanted her to dance like a melody on a violinís strings.

He wanted to see in her lap the milk-stained mouth of a sleeping child.

He looked after her like day-old bread to be relished.

He was trying to save her from the barbed wire around Albania or Siberia that bloomed like flowers from stone.

He loved her more than his country but lost her far away like his dream,

the same as a young man of his enemy country.

Nicholaís Mother

Her world is only as large as her bread, her sky the blackbird flying across the window, all juices for her start and end with grapes.

She stands on her toes and starts to twirl.

Borders draw and redraw themselves across her chest, languages peeping and pecking grains from the palm of her hand.

Sheís been so many countries without ever moving from her axis as Nicholaís mother.

*Nichola is a Macedonian poet and his motherís home has been ruled by three different countries in her lifetime Amzad Aliís Sarod

Amzad Ali lifts the sarod to his lap like a jumpy rabbit and slowly begins to stroke it. With a hiccup, strings clear their throats then a gamaka bites, sharp as a knife.

Amzad Ali closes his eyes in the glow of raga while Night Queen wakes from the magic box, peeking out at the jhinjhoti strutting its nine-beat swagger.

In that instant, I see a cry, my chin cupped in my palms as I watch the sounds of music dancing, my eyes numb, the rhythms captured in the clap of the tabla as it weaves its silk.

I watch the cry flutter with each note, and I lose track of time, canít tell if anyone else here sees through blind eyes.

Iím carried away by Amzad Aliís rendition of ďLet Us Walk Alone,Ē and I forget the cry, which falls asleep like a small child sucking her thumb.

And though Iím freed now to enjoy Amzad Ali, the sound of the cry resurges, suffusing the jhinjhoti and ďLet Us Walk Alone.Ē

Cries call me now to the town square, where they become flags draped on bushes like dusty rugs. I want to reconnect the broken strings of the great teachers, drowsied, half-strangled by the coiling serpent

of rhythmic waves of music that make us deaf to youthful cries.

Amzad Aliís sarod doesnít know the language of the deaf,

and Iím almost deaf with the non-cries of this crying.

Roots

An itch in the sole of my foot reminds me of my roots

and while searching for them I wander aimlessly

though theyíre not very far: only five feet and a few inches down

not very deep, but they shift in the evening so by the time I draw near, my soles are disappearing into their own shadow.

Migraine

A woodpecker hooks its claws into my temple and pecks into my brain, his beak snatching up the tiny worms of my thoughts and attachments.

There is no fixed date for the arrival of this woodpecker, who instead of fruit prefers the dry wood of brains, devouring my every thought.

I close my eyes to his tuk-tuk pulsing in my veins and disappear into the bird.

A Thread Is Being Spun

A thread is being spun a seed sprouting the earth waking and the sky is turning into trees meanwhile a small sparrow flutters down, lands on a finger on my left hand

*

You, a shard of light You, the dew on a thornís tip a sprout in parched earth a secret told in goose bumps like a clairvoyantís vision

You have come to me

Against all the souls severed in the womb Against a lake of a thousand sounds buried in deep waters

An earthworm burrows into a ditch A conch writes a word The thread of a web snaps, is broken

*

I try to read the letters of dreams written on your eyelids want to learn the script written long before civilization emerged from the Indus Valley scripted in its streams between the mountains and rivers

I want to dip my faded paintbrush in the colors of your dreams absorbed from the sky by trees before taking birth in the earth

I want to write a poem soaked in the gurgle of your innermost soul like an oil-soaked wickís dancing flames

And in this I wake with the heavenly music of the unstruck sound hidden deep inside my navel

*

How do you recognize the tunes the hidden rasas the mind and spirit the sounds produced against classicism how do they become sweet as milk upon reaching you your eyelids becoming heavy as you listen to my lullaby

how do you weave dreams with the words of sleep and how do you find the meaning of whatís not there but spread like a maze of tunnels until reaching the past where you and me converge in a single point

Iím perplexed!

*

I spin your cry into a thread I embroider your smile onto the weave and I see in you the face of my mother who stretches her feet out under sunlight counting moments of peace with closed eyes

She sat spinning golden rays of sunlight visible to me only from a distance looking disinterested with a strange enmity an incomprehensible stiffness in her fingers or pain in her knees I never longed for her hug

You smile between the cries and I kiss your forehead as if kissing the painful fingers of my mother

In her half-woven sheet mother descends four steps and sits on my lap

I find in my cupboard two masks nearly thirty-years-old a bit dirty but firm as new ones

Your mother dusts them to be decorations and hung on the wall they begin to smile freed from thirty years of prison

I wonder if mother too smiled that way when getting up from her cot and hanging on the wall

You learned to respond to the smile

I want to get rid of all the debris and rubble of the world want to remove all the nails so that your smile can spread like morning sunrays

*

History I do not know the history you wrote on horses during war

I donít accept the books that test you on religion and spirituality

I ignore the cobwebs that constrict my neck with their red and blue noose while I feel the whip of the Rajiya Sultan the neighing of Lakshmibaiís horse in my mind

I like to think of all the brackets that still confine people of the drugs that have fused our brains of that shriek still stuck in the throat

History has never been my friend

*

I did call you a parcel of sun rays I will close you in my fist and then open, so slow you can weave a silky thorn on your body Then Iíll toss you gently towards the sky so you can open your wings yourself

You shall fly without forgetting to crawl then crawl while flying

and search for all the answers to all those questions in the eyes of my mother as question marks moments before her death.

Stray Dreams

Each morning my dreams begin to wander around

They know where not to go Destinations are never marked in their plans

They donít go to Fairyland The beauty of the stars doesnít attract them either

Among those living on Earth they love only black ants which are not less than elephants

Trees and birds donít attract them

Their most interesting practice is to trail running cars

Abandoning cities and villages they reach those satellites where live those we in our languages call the dead

The story of dead people is different too They donít recognize the new ways of life and go gossiping to the dreams

By night the dreams return home

and place their bundle on the stump in the middle of my mind where they themselves sleep

the bundle opening me awake in my nights with its gifts

Varicose Pain

A few ants traipse down my thighs to the ground, bottling up in their mouths the dreams of those saved by living.

Leaving behind blue oblivions they descend further.

Pain melts in their mouths in thin blue smiles.

I encompass the pain in soles consigned to earth.

Varicose Pain II

Within my torso two bags huff and puff filled with the tedium of things

Among the boredoms is a list of work that exceeds my limits

I donít know which worthless law decreed me this list and I, a fool in the night, have forgotten that I myself am not even on the list

My swollen veins question meó bang-bangó and I rub my feet with my hands to keep the cries beneath my tongue

Knee Pain

Above my calves two oleanders bloom, piquant and climbing all aggression, tireless, till they morph to hibiscus with biting pain on these axes like a bobbin

Until time blossoms on my palms Until the lines open up twin pains wake in hibiscus and control my journeys

Still I walk, two stars on each calf, forgetting the count of destroyed time

against all the pain centralized just below my thighs

Spiders

On the back of each of my hands a spider climbs weaving the warp and woof from neck to feet I think only of mother

I donít remember Kabir and his sheet donít even remember the two girls singing a hymn to Prana

I think only of mother and her veins soaked in oil I put my palms on my lap and stroke them as if they were motherís forehead

Time Near To Me

Today I woke late and ignored my cup of tea reading an unknown poet from Lithuania. His poems were open like a glass jar and my words began to fill the gaps between them.

Today I ignored the dirty dishes in the sink, didnít bother to fold the washed clothes. I turned on the TV, flipped channels, and let my room fill with many voices.

When words took flight from my fingertips on the keyboard, birthing a poem by computer, that movement ďtimeĒ wandered around me like my tame dog. The Wings of an Ant

They say an ant has no wings and that even if she did, she couldnít fly.

And if unable to fly, why suffer the pain of wings?

The antís death rides on her wings, but death itself is flight.

The ant started to fly by pale blue light, bending her wings to the south, an illusion of silence amidst noise.

Towards the yellow light, she flew against her life, carrying flight in her every cell.

She saw the seeds of flight for the next generation.

When he plays the drum,

the sea steams and his belovedís brow beads with sweat,

when he beats the drum, huge stars implode and the curtain flickers in his belovedís window.

Sweat-soaked pain sprays out from his beating drum, the Earth losing its way,

a small bird landing on his belovedís roof, her hair showering down, the trees bathed in its sweet perfume.

The Swamps of Alzheimerís

1

Her trembling feet inch forward into the future, they slip suddenly, she falls into the past, starts to chuckle, Look! The trees, theyíre talking to me, and she starts chatting with branches, the leaves of the Neem tree, in the courtyard of grandfather. I pull her back with force from the heights of coconut trees and she gets irritated, runs to words, granduncleís storeroom, where she searches for inked addresses long wiped clean.

I pull at her and she becomes again and again a little girl, mother in the swamps of Alzheimerís.

2

Itís my turn, Iíll comb your hair, youíre pulling mine, apply more oil.

Raking fingers through gray thin hair the daughter thinks of the little girl grown up and the old mother changed into a little girl.

3

These days sheís upset by riotous memories, whatever happens now is wiped away, a crowd of memories rushing backwards.

Sheís forgetting the meaning of key words, forces her way into stories, sometimes sleeping, sometimes hiding in the kitchen pantry.

4

After wetting the bed she tries to hide it with a pillow, inspects it and smiles like an opening bud, even after a scolding mischief swims at the corner of her lips.

O, is this my mother or a careless little girl?

5

These days everyone talks to her, each chair, table, and box, they come to her room, dogs, lions, and leopards, without fear she plays with houseflies, dances with ants, mother a friend to everyone who cannot be seen by we, the intelligent.

Like a kite slipping from hands, mother drifts through the swamps of Alzheimerís. Remembering the Camps of Exiled Kashmiris

These days Iím forgetting a number of things: a pen, spectacles, and sometimes I canít even recall what Iíve forgotten, but today, after two long years, I can still remember well the exiled like the memory of my own mother.

When I met them that day, I recalled mother, a woman often compared to them because of the color of her skin and her pink lips. I met them again and I thought again of mother, who still looks like them, her pale, dull skin, her lips.

Mother lost control of her legs then her arms, and finally her neck; bedridden, unable to talk, sheís full of wounds and waste.

They first lost their feet in their land, then their arms were pinned down by a political system; their voices taken away by hunger, their hearts filled with bloodshed. One can see their wounds in their eyes.

How strange after two long years to recall them as clearly as the sky on sunny days, suffocating sounds come from motherís throat: ghon, ghon.

I get restless and think of them, I think of a new bride wrapped head-to-toe in a red sari. I remember the windowless room, the ventilator, fifteen family members packed in there. I choke on the thought of a newlywed couple waiting to celebrate their marriage.

I remember mother when I recall the eyes of angry youth, a number of questions on their lips.

When I think of their exile I cry for mother, forced to live against her wishes in her daughterís home, forgetting to die.

Why do I mix mother with them when in many ways they share little in common? I ask myself and begin to cry for their land, their sanctuary, my flood of tears washing motherís feet.

The Sea

1

The sea is quite different from the sky, different too the clouds from one another, but when, as she stands on the shore and he takes her in his wavy arms, wets the hair strewn across her face, fondles her thighs, lays his head at her feet and looks up at her, where, then, is the difference between him and a starved lover?

2

Every evening the sea gathers the sacred wood of clouds, strikes the holy fire of the sun, and sets out an offering of waves to conjure its black magic, every evening the darkness comes from that magic, spreading the news of a conspiracy, and from that conspiracy this world has grown.

3

As evening withers a star sprouts on the sea, with a finger at his lips he bids everyone quiet, says Be careful, youíre not the only one alone, weíre each alone in our own sea.

4

I saw him and the sea that evening, he was bobbing in the water, the sea flowing over him.

He saw me and the sea together, the sun sinking into the water, and me sinking with him,

each of us sinking into the other.

5

In the quiet black of night, the earth grows a ray of light,

whatís unusual is how the sky hangs lamps of light each night, looking at the sea he stays behind, blows the line of light into an oven burning across the sea.

6

Somebody says Itís an open sky, open as an opened fist.

Somebody says Itís a deep sea, deep as the heart of man.

When I saw it it was an empty canvas without a single scratch.

7

Itís the sea, smell of bodies, of floating light, the smell making nostrils flutter like fish darting through water.

The smell enters every pore like pieces of shell and the body changes into a sea of smells.

8

Keeping innumerable colors close to his chest like floating lights and laughing rocks how lonely the sea is who knows?

Even the sea doesnít know his reverberations, the waves laying their heads on the shore, bursting bubbles whispering into ears how lonely the sea is who knows?

9

The sea is getting wet in the rain laughing like a desert child,

the sea is getting wet with its own tears smiling like a young woman sitting on an island,

the sea is getting wet with a shower of love: his sobbing pain at getting separated from his loved one,

the sea is getting wet in the first rain after summer.

10

The smell of the sea is different from the soil wet in the rain, has no relation to the smell of flowers, doesnít know the sharp taste of passion.

The smell of the sea doesnít enter through nostrils but through every pore, touching gently, hypnotic.

The smell of the sea speaks the story of the sweat of fishermen, the play of sea life, the legends of ships.

Old Lady Talk

The old ladyís stomach was a drum of chatter: rat-a-tat here, yippity-yap there, playing so long loneliness passed her by without even knocking at her door.

Then one day she went quiet. The sun rose; she said nothing. The moon bloomed; she stayed silent. Wind, flower, ants, lizardsó all came and went, the old lady remaining silent.

People say that was the time of the great collapse of walls between heaven and hell.

Tongues

My mouth teems with tongues of many tints and flavors, similes and metaphors.

At first I had one, just one that I fastened early each morning and gave over to sleepís care each night.

I donít recall when it split and branched like an aloe plant, dividing into two, three, four sections.

All these tongues talked even in sleep, causing days to lose their count, and striking the dreamworld dumb.

And in the midst of so many tongues I had none.

Cry

My cry finds no place on Earth nor in the sky and so seeks shelter in my chest, my belly and thighs, my womb.

They fear my cry and so rip at my skin with nails, wishing to remove my womb.

I bury my womb in the earth and stand still until turning into a tree that grows with thousands of cries against the nails of artificial civilization.

All this can begin in a single cry.

A Faithful Prayer

Deep love cannot surface during faithful prayer. Itís a sin think of love while praying. But prayer within love? Thatís the greatest virtue!

The language of the poetry

At the tip of my penís nib is a colander. My words sieve through it like fine sand: a few words, a few spellings, and a few meanings always stick to colander, turning the language that makes it through babble the critics say. The language of poetry cannot be babble. Grammarians do not accept the language even I scrape the stuck spellings, meanings, and vowels from the colander and blend them into language. Itís still not poetry because itís plastered with corrections. So I leave the language and colander and take only expression: I fly it as a kite into a sky of emotion. Now a poem can walk the earth and face the sky. Now thereís no colander on my pen and no critics look at my poems.

Refugee

They came to this land as if by sea, the way wind clings to spar, like the dew on a humid morning somewhere near the equator or the way moths on a rainy evening fly towards the light, they took shelter in this place the way wasps nest in the holes of old wooden doors, or a letter with a wrong address in a post office box or unwanted email in an inbox, they settled in this land the way ice floats in a glass of juice, like kites holding tight to the ruins of buildings, they return each night by marshy paths where their footprints stipple the land like goose bumps, their hunger stubborn as the blackened ash stuck to the bottom of a pan, one step backward to lurch one forward they disappear into the land that does not belong to them.

Laughter Is a Prayer

Laughter is a prayer needing many intonations to go from chortle to song.

The chortle wakes the gods, but its the first note of song that connects with time.

The second note of laughter flows from the eyes, not the lips.

Laughter is a prayer against all unrepeated prayers and against all deities who dare call my laughter uncouth.

-----

The Aroma of Spices

1. Poetís Pyre

In a blindfolded world I beat the deathless drum óBhikku Nanamoli

This is not the first poem Iíve taken from the dusty old file despite the many fresh ones redolent of new earthen pots

But Iíve taken this one Agnaye swaha! the primary offering for the pyre the journey into your being and not being is not so difficult

You were here till yesterday in the yellowness edging the leaves in a pen between my fingers in its scratches on paper in the the wind rolling through my fan in the aroma of spices filling the kitchen youíre still there though the pen stand is empty dried leaves have fallen and the aroma from the kitchen is gone

Agnaye swaha! this is the second offering I make for your pyre the boat is in the sea the net is in the boat the fish in the net the fisherman killing the fish blue is a shade that fades a boat can sink I am fish for your net

Agnaye swaha! this is the third poem the last offering for your pyre

Youíll remain in the verse in the remains of the poetry we wrote together

remember?

2. Marks of Decay on New Moons Day

When I meet the right consort my thoughts become clear óChogyam Trungpa

This time again youíve given yourself up to prison have walled yourself in and now live in a heavy dungeon where there arenít even cracks to let me in as air and where you shine like a sun giving light to your own name

This time youíve cheated on me! I who warmly kissed on your feet and stroked your whole body with my eyelashes

Last night on my window sill I saw marks of decay of creeping death of my poems ending the corpses and my fingers stiff with pain in my neck and shoulders the cracks inside me aching my body at war as I turn from river to blood

3. I Fear Thunder

Sesame oil is the essence. Although the ignorant know that it is in the sesame seed, They do not understand the way, effect, and becoming. óChogyam Trungpa

For a while a smile has danced on my lips like a butterfly but I know thunder will come and freeze them Iím afraid what will happen when it roars me awake?

The paths are disappearing and in the undergrowth shadows emerge and on the tips of tree branches a thousand deaths wait to take flight as one Iím the vulture preying on the bird of love I dip my fingers in its broken feathers sweep away the remains which disappear into the holes of snakes O look at you, a half-broken branch about to fall!

Youíre an illusion in my hallucination as Iíve known for quite a while youíre selfless selfishness! Iíve learned this from your company Iíve discovered how youíre my myth which cannot be abandoned I learned this in all the trials to forget you

Do I leave the company my pen? Iím sinking in its ink how do I search for Nirvana in the eye of a needle woven into the colors of the flowers?

4. Embroidered Flower

The birds warble their glad songs. Spring blossoms in the treetops. óLouis Nordstrom.

A long time ago I sent you the aroma of flowers stitched to my sari through the cracks in the walls of a castle embroided by thread Iíd colored

5. You Are Mehandi, The Henna of Full Moon's Day

How much more so when perpetually diseased By the manifold evils of desire? óShantideva

How strange to have discovered my feet only after walking almost half of the way to you!

And now on the road to red lotuses where my heels once taipsed there are blossoms between my toes red flowers of fortune!

I love my feet as if they had faces oh donít stroke me with your fingertips, friend, donít bite me you who sent me henna to adorn my feet I draw flowers for you on my feet vasant spring already here the sun shining stripping off his sweater, my love!

Shishir is the wintry time of ice falling from the heavens greeshm is the green shimmering heat on my shoulders I am ready to journey first stretch a fingertip to toe my journey is a flash of pink my journey continues and continues toward you

6. Donít Decorate the Pyre

The trees and also the great woods All are made splendid in the 10 directions óEdward Conze

Iím not a river and so donít need mountains to give me form Iím a lake! The sweet lake honey lake in the lap of the desert my womb never goes dry never moves from here to menopause

No, no my lover! My lover! You canít light the pyre with the pallu of my sari itís for the children the laughter of my children who are tickling me as I dance laughing

Look! Oh look! I am not a dried up water reservoir Iím the lake my womb is water this world is inside me!

7. Cuppa Chuppi/Hide-and-Seek

In the sea of my mind the words as waves have risen In recollection of the Great Queen óChockyam Trungpa

Lake! O dear Lake! Play chuppa chuppi, play hide- and-seek with me! I turn and run from Udaipur hide behind a coconut tree where are my friends? where is my playmate? where is she? oh this isó I got her! chooooooo!

Time passes days weeks years Iíve forgotten to show myself! forgotten! like Iíve forgotton the way I first came to you my dear dear lake! where are my friends? where are they? where is my playmate? oh this isóchooooooo! will you come looking for me? Iím sitting in a shrub of thorns

8. Hands on Shoulders

I go to Kasiís city now To set the wheel of law in motion óBhikku Nanamoli

ďRivers may split and reconnect but friends never meet again in lifeĒ Come O Lake friend and put your hand on my shoulder Iíll keep mine on yours come let us gossip about the village girl who fell in love and split with the weaver boy let us weave the thread of gossip as long as the threads of memories

9. Anklet Bells on Protector's Day

Dancing in space Clad in clouds Eating the sun and holding the moon, The stars are my retinue. óChocyam Trungpa

Come swim in me come swim with me come wash away your dirt how much of it can you carry on your journey towards lifeís end? when night falls on me a thousand dancers emerge to dance for me dhinna tak dhinn lotuses bloom on their feet white lilies blossom on their toe rings come to the shore of this lake touch my body with your poised finger Iíll bloom into a hundred lotuses see, Iím blushing

Donít worry, my pilgrim! Iíve discovered all of my feet time and again Iíll give you my part of the journey Charevehi! Chareveri! keep on walking my loving traveller and donít tire

10. Small flowery marks of lotuses

Rain, sleet, snow, ice - as such they may different, but when melted, they're the same valley stream water. óThomas Cleary

That evening at godhuli that evening when the cows were returning when the temple bells were ringing she came out from hiding behind the mango tree there she is Ė there! taking a baby girl up in her arms a baby girl pockmarked with small flowerbuds lotuses tied to her feet O where will I take these girls?

Look at the bird its yellow beak thatís my baby girl with a ribbon sheís in the tree she flies she sings and when she dives through the sky her beak turns blue and when she dips it in the lake it turns everything blue and fresh it was just yesterday she had a red berry in that yellow beak firey as the sun squirrelike she climbs a tree gifts me a mango seed

11. The Singing Mother on Dakini Day

In the sea of my mind the words as wave have risen In recollection of the Great Queen. óChockyam Trungpa

are yours my

son

Mother used to

sing on rainy days

Iíll be the

parrot in your garden

why did you

send me away?

12. Pain Like a Blanket Eating the sun and holding the moon, the stars are my retinue. óChogyam Trunpa

The aroma of

spices

The day, is

it or mine to you?

A yellow day

13. Tale of the rain girl

May the Ocean benefit óChockyam Trungpa The farmer girl sings

Give me rain,

Black Cloud! give me rain sugar cane and puffed rice

my crops are

dry of rain peacocks dance on her thighs streams swirl on her hips white lotuses blink on her toe tips the night hides in her black skirt the sun and moon in her blouse

Give me water so my beloved wonít be thirsty

Of what comes after Pralaya

the doom

Didnít I tell you it was there? You could have found it without trouble, after all.

óLouis Nordstrom.

Yesterday I

took some photos

my running feet you know: the ordinary one!

Translatorís Note: On Dreaming in Another Land

In discussions of literary translation, one often encounters the claim that it is impossible to translate poetry. That is, at some point in conversations about the translatability of poetry, someone will opine that it simply cannot be done. Typically the speaker means this linguistically: poetry in one language, with all of its rich and layered denotative and connotative depth and resonance, cannot be rendered adequately in another. But such a claim is more properly an interrogation of adequacy than possibility, no?

Other rationales for claiming the translation of poetry to be impossible foreground cultural, aesthetic, and/or political emphases. For instance, one hears relatively undertheorized claims about the incommensurability of cultures, the lack of aural equivalents between languages, and the untranslatability of metaphor due to both the intrinsic and relational instability of both signifiers and significations.

But to my mind, regardless of the specific terms of its instantiation, the assertion that poetry is untranslatable is as dull as it is glib, and it may even be downright dangerous. For, from my perspective, claims to the untranslatability of poetry are foreclosures of possibility. They are a violent censoring of communicative potentiality, disallowing new modes of being, new modes of perceiving, and new networks of solidarity.

Why, then, are claims to the untranslatability of poetry so prevalent in literary discussions and beyond? One answer might be that these claims abound due to the relative difficulty of theorizing, practicing, and understanding literary translation. I would therefore like to offer some introductory remarks about the translation of poetry, including the efforts that have resulted in the book currently in your hands.

To begin to theorize translation in relation to poetry, one might consider how poetry is always already translation. This is evident in Rati Saxenaís work, and a clarifying example might come in a poem of hers included herein in translation as ďThe Sea.Ē In the original poem, one notes how the lines pivot upon metaphors built of a linguistic blend of Sanskrit and Hindi. That is, Sanskrit words like ďsamidhaĒ and ďhoma kundĒ propel that poem, in part by transfiguring theological significance transhistorically and transculturally through poetic imagery. That is, the poetic verve emerges from the linguistic energy born of the juxtaposition and integration of two language traditions into a contemporary, comprehensible Hindi syntax and speech, which invokes a vibrant historicity, theology, and politics through extended metaphor.

And perhaps this fails in English-language translation. Perhaps the intricate hybridity of the original poem is mismanaged and muted in ďThe Sea,Ē wherein the contemporary Hindu reader in India might lament the lack of Vedic resonance, for instance. That is, the translation might compromise the complex pastiche of theological, historical, political, epistemological, cultural, and ontological markers that create the symphonic beauty of the original poem. Of course such imagining problematically presupposes the existence of a singular Indian reader, not to mention a singular reading of the poem.And, more broadly, arenít such normativizing presuppositions and insistences antithetical to very nature of poetry, which aims to expose, disturb, unbind, and disrupt the violence of normativity?

Consequently I would suggest most generally that the translation of poetry is not an impossibility but an emergence. It is a praxis of poetically formulating the conditions for the realization of resistance and alternatives to dangerous logics of purity. It bears mention, too, that such logics are purposefully exposed by Ratiís work. In other words, the plurivocality, transculturality, and transhistoricity of Ratiís poetry are its defining features, so to argue for purity in the face of her poetry is to misconstrue it. More generally, to argue a logic of purity is to perpetuate an essentialist ideology, with all of the fascistic imaginative heft that such ideologies entail, and that doesnít seem propitious for poetry or people.

In other words, readers of poetry are gifted the opportunity to reckon the hybridity of language. This is as true of so-called original poems as their translations. In both cases, the poetry compels careful readersto think through the mobility, elasticity, and vitality of language(s), which demands continuous attention to transformations, excisions, invocations, and extensions. This is another variation on the aforementioned idea of language being in motion; it is always already translation. After all, isnít that one of the key promises and possibilities of language? Doesnít the poem offer itself as a mode of emerging through new networks of discursivity via the orchestration of language(s) via the manipulation of the tropes and figures of poetry?

In this manner, Ratiís translators must grapple with the importance of the aforementioned example of her blend of Sanskrit and Hindi, for instance, recognizing the original poem as always already a translation. That is, even before its translation into English, for example, the poemís language is already hybrid, forging and extending translingual, transhistorical, and transcultural affinities and possibilities. How else to reckon the resurgence of Sanskrit in a poem reinvoking the Iron Age in northern India to speak in twisted tongues through the syntax of a contemporary Hindi, feminist poetry emerging from southern India during a twenty first-century crisis of globalization?

More deeply, Ratiís invocation of sacred Sanskrit signals both a return and departure. It enacts a subtle and intricate historiography of linguistic transformations in the service of theological reflection on the past, and it concurrently enacts the past in order to challenge the conditions of the present. Moreover, in challenging the present, the always-already-translation of this work serves to effloresce and ramify the possibility of the future. In other words, it necessarily postpones the future by contesting the present through rememorations of the past.

And this disordering of time offers itself further as a point of consideration for me to clarify my theoretical interest in translational poetics in general and my work with Ratiís poetry in particular. From my perspective, the translation of poetry, hers or otherwise, is precisely a possibility because it struggles towards the horizon of escape from the censorious and oversimplifying rigidity of (false) binaries, such as original/translation, purity/impurity, self/other, male/female, etc.

That is, to think translation impossible is to reassert predetermined taxonomies. Meanwhile poetry aims differently; it aspires to expose, undermine, and escape the tyranny of such rigidities. To claim the translation of poetry impossible, then, is to reduce the potentiality of poetry. In other words, language exists only through its actuation, and the limits of language are therefore the limits of possibility, meaning here the limits of world(s).

This is not to hyperbolize or melodramatize the work of poetry and poetry-in-translation. Rather it is to emphasize the theoretical underpinnings of a praxis of translational poetics that understands wor(l)ds as infinitely prismatic, schismatic, and adaptive, meaning they are riddled with irruptive potentiality, which is the possibility to conjure entropy, to create through emergence.

In other words, the work of translating poetry is not an agonistic process of immersion in the irresolvable tensions between antinomies. Nor is it an impossible struggle with incommensurable binaries that cancel the art as aptly as the audience. Rather translation is a faith in the possibility of transformation and emergence. It is the promise of the possibility of future(s), meaning an opening of formerly foreclosed potentiality. It is the blossoming of possibility returned, a (re)discovery and (re)articulation of form from within itself, a chance to surge forth and illuminate former absences and previous erasures of potentiality.

Thus translation can stand as a horizon of possibility for the recuperation of self. And therein lies its initial impossibility, which is undone, or released from stasis, by its reckoning through a translational praxis. In this manner, translational poetics also signal a foundational condition of democracy; it is a mode of thinking through the non-subject, she who has been pushed beyond the frontier of legibility through a series of sacrificial violences. And here again Ratiís poetry might prove clarifying.

Specifically Ratiís poetry explores these sacrificial violences, or erasures of subjective possibility, via her poetic revelation and consideration of gendered, economic, political, and intellectual inequalities. Moreover, through those poetic renderings, we can theorize the potentiality of a translational poetics. It is engaged in the study of apparition from and through absence, lack, negativity, and erasure. So in working to wrest an English-language poetry from Ratiís gorgeous already-translations, a translational praxis extends Ratiís effort to cancel former failures, disappearances, exclusions, and censorships.

It is a politics of exposure, then.It is a belief in the value of grappling with the concept of legibility. In the case of translating Ratiís poetry, that legibility emerges through a process of discovery, meaning one could not foreknow the eruptive force of the poetic realizations to come from translating. Otherwise they would be merelythe formulaic promulgation of preconceived logic. Instead the translational poetics created the conditions for the emergence of new possibilities, and this came from working closely with Rati in a diversity of forms and media, including the continuous re-reading of her poetry in multiple languages, listening to recordings of her reading her poetry in Hindi, and talking with her in person, by phone, by email, and by Skype.

Of importance, each of those modes of reflection and discussion engendered its own temporalities, meaning its own synchronization of absences and erasures, whether they be attributable to the miscommunications of multilingual conversation, the absences intrinsic to phone calls due to their disproportionate emphasis on disembodied voice, the delays and gaps in email conversations, and/or the insuperable silences and forfeitures intrinsic to working by Skype across a dozen time zones and with inconsistent Internet service. Of course this stammered, multimodal network of conversation of and through poetry was facilitated by Ratiís unflagging grace, patience, and intelligence, which time and again made clear to me the unclarity of worlds, and the potentiality of poetry or, more properly, poetry-in-translation.

So please join Rati now and struggle to realize through her always-already-translations some of the possibilities for rupturing the false constraints of the subjectivated being, whether they be grounded by gender bias, economic exploitation, hawkish militarists, ontological dogma, or otherwise. Ratiís way is the way of irruption; it is to live by availing oneself to the violence of re-emerging, of realizing oneself by destroying her through the languages of new potentialities. It is an ontology of dreaming the self in another land, with that concept having everything and nothing to do with travel. Ratiís poetry encourages valiant defiance, a courageous challenging of the capture of the subject. And she first and foremost makes this possibility known poetically, as this book makes clear.

This book dares to dream in another land, through and of oneself, who is many, meaning you are traveling alone and with other selves, yours and otherwise, via Ratiís animated and vital poetry, which cleaves possibility from deep within the word. She risks everything to transform it, understanding the importance of entropy, and trusting that what was sacrificed might return: through her, of her, from her, and for you.

óSeth Michelson Lexington, Virgina, U.S.A.

Rati Saxena Ė Poet/ Translator/ Editor (kritya) / Director Poetry festivals-kritya and vedic scholar. She has 11 collections of poetry in Hindi and English and one each in translated in to Malayalam (translated), Irish, and Italian, and English by other poets. Her poems have been translated in other international languages like, Chinees, Vietnam, Albanian , Spanish, Uzbek. Indonesian etc .She has a travelogue in Hindi- ďCheenti ke parĒ, a Memoire in English-ď Every thing is past tense ď. a criticism on famous Malayalam Poet Balamaniyammaís work. Her research on the Atharvaveda has been published as *The Seeds of the Mind--* a fresh approach to the study of Atharvaveda, under the fellowship of the Indira Gandhi National Center for Arts. She has translated about 12 Malayalam works, both prose and poetry, into Hindi and two from Norwagian languages. she has participated in several national seminars and published articles in a number of journals. She secured the Kendriya Sahitya Akademi award for translation for the year 2000. She has been invited for poetry reading in prestigious poetry festivals like "PoesiaPresente" in Monza (Italy), Mediterranea Festival (Rome) and International House of Stavanger (Norway), Struga Poetry Evening (Mecidonia) , and '3rd hofleiner donauweiten poesiefestival 2010, Vienna , the prestigious poetry festival in Medellin (Colombia- two times), She is the only indian participant in some imp poetry festivals like - Iranís Fajr Poetry Festival , International Istanbul Poetry Festival (IIPF) Turkey, 4th international Eskisehir Poetry Festival. Turkey And in Chinaís Moon Festival and Asia pacific poetry festival 2015 Hanoi She has been invited to some American Universities also to talk about Vedic poetry and recite her own poetry like Mary Mount University in Loss angles and University of Seattle ( USA) , She is one of the three representatives from Asia for World Poetry Movement, which has 37 foundation members around the world. She is the only Indian whose poem has been chosen in popular book of china Ė 110 modern poems of the world.

Seth Michelson is the author of the poetry collections: House in a Hurricane, Big Table(2010); Kaddish for My Unborn Son, Pudding House(2009); and Maestro of Brutal Splendor, Jeanne Duvall(2005). His latest book, Eyes Like Broke Windows (2012) won the poetry category of the 2013 International Book Awards. His translation of El Ghetto, Sudamericana(2003), by the internationally acclaimed Argentine poet Tamara Kamenszain, appears as The Ghetto, Point of Contact(2011).His translation of bicho bola, Yaugurķ (2013), by the Uruguayan poet Victoria Estol, appears as roly poly, Toad Press(2014). Seth Michelson holds an MFA in Poetry and a PhD in Comparative Literature, and teaches the literature of the Americas in the Department of Romance Languages at Washington and Lee University in the United States. His scholarship appears internationally in a variety of venues. He will be finishing his two academic books, The Poetics of Re-emergence: Poetry, Subjectivity; Political Violence in the Neoliberal Age; and Decaptivating Bodies: Prison, Politics, and Literary Production soon.

T P Rajeevan

|